|

March 10, 2015 CC BY 4.0 |

print comment |

Keywords: archive | big data | cold war | politics

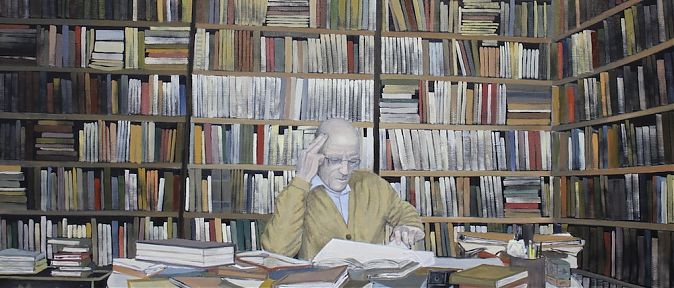

Michael Burris Johnson: Cage (2013)

Until March 19, 2015, when our conference "Historicizing Foucault" begins in Zurich, we will consecutively publish the abstracts of the accepted presentations. Jason Pribilsky, Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Whitman College in Washington State, USA, will talk about "The Will to Enclose: Foucault's Archive in the Cold War Era of Big Data" in the panel Foucault and Politics on March 20, 2015.

The idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity. [1]

By the mid-1960s, Michel Foucault had largely sketched out his concept of the "archive" as "system[s] of discursivity" – the sedimentary and stratigraphic layers that required an archaeology to follow power-laden genealogical pathways. While the concept belongs to his methodological toolkit, Foucault made clear the political implications of mass collection and codification. In the quote above, taken from a 1967 lecture, Foucault suggests various possible connections between knowledge's accumulation and the project of modernity. This paper will explore Foucault's fashioning of the concept of the archive as a product of modern power within the context of archival practices emanating out of the early Cold War.

This period (from roughly 1949 to 1970), as much recent scholarships explores, was overshadowed less by contests over military power and more squarely focused on competing styles (Soviet and US) of how best to development and modernize the Global South. Such geopolitical concerns saw the feverish acquisition of "big data" (cross-cultural surveys, databases, etc.) as well as the technological innovations to facilitate it (computer punch cards, cybernetic networks), all in the service of revealing the key factors and drivers that would lead all so-called "backwards peoples" through universal phases of modernization. To be sure, as Foucault's thinking on the archive was taking shape (developed most fully in The Archaeology of Knowledge [1967]), movements within the early evolution of the global behavioral sciences (political science, psychology, anthropology, among others) were compiling the archives that would produce compelling understanding of human's true nature, considering everything from competitiveness to creativity to economic outlook.

This paper will ask: How can we read Foucault's concerns about "infinite accumulation of time in an immobile place" within the context of the early Cold War and the globalizing behavioral sciences? In what ways did Foucault's writing about the archive, often interpreted as a commentary on the 19th century, emerge from the context of mid-20th century, decolonization, and the "total history" of modernization theory's promises? In what ways are Foucault's writings on the archive a response to the rise of "big data"?

[1] Michel Foucault [1967] "Of Other Spaces." Diacritics 16 (Spring 1986), p. 26.